https://www.katiecrim.com/episodes/ciuvuhzlriyl885iczsl5adeg5awj2

Interview on Simone's Songlines (English/Nederlands) →

https://radio2.nu/RamaKumaran

DE SONGLINE CHOICE VAN RAMA KUMARAN

21 november 2019 16:44

Deze week is de muzikant en verhalenverteller Rama Kumaran te gast bij Simone! En hoe komt ze eigenlijk altijd aan haar interviews? Simone vertelt het in de podcast.

Op een koude herfstdag dwalend door de straten van Haarlem komt nomade Simone Walraven van alles tegen… Hoe komt zij toch altijd aan die mooie gasten, ze verklapt het in deze podcast. Tevens een bijzondere ontmoeting met muzikant en verhalenverteller Rama Kumaran uit Nashville. Hij studeert aan het conservatorium van Amsterdam, wat bracht hem hier? Een verhaal over roots, bijzondere plekken, een vroege muzikale herinnering én jammen met Shakespeare.

Article in THE GAZETTE (Croton-on-Hudson, NY)

Excerpted from The Gazette Vol. 36, No. 25 (Week of June 20 through 26)

by Cornelia Cotton

“Also at the library, a very special treat: the immensely gifted young flautist Rama Kumaran in a program that showed off his enormous versatility. Rama won the National Flute Association’s Young Artist Competition — the youngest winner ever. After demanding pieces by Debussy, Poulenc, Faure, and the thrilling “Carmen Fantasy” by Francois Borne, he tackled “Voice” by Toru Takemitsu, the late, great Japanese modern master. This fantastic composition, testing the limits of the flute’s possibilities, was influenced by John Cage, the American avant-garde musician. It incorporates spoken words, shouts, and what sounds like the instrument being knocked against the teeth of the performer. He was accompanied by another prodigy — Jack Coen, who had been music director and organist at the Holy Name for several years. He is much missed. It was a treat to have him back for this rare recital.”

Article in Vanderbilt News Magazine

https://news.vanderbilt.edu/2019/04/11/musical-talent-and-mentor-rama-kumaran/

by Bonnie Ertelt Apr. 11, 2019, 12:00 PM

Lecture-Essay for "Love and Music"

Introduction: Subitizing

https://blog.wolfram.com/data/uploads/2011/05/subitize.gif

There’s an article published back in the mid-20th century coining a new word, “subitize.” Breaking it down, the word’s first root is the Latin verb subitare (“to arrive suddenly”). That word gave us the musical marking subito, i.e. subito presto, “suddenly quick” (when we’re jolted out of a lull). The second root, -ize, is Greek. This is because, as the authors confessed, the corresponding Latin suffix sounded wrong. “Subitate,” an all-Latin word, was too close to too many other English words; it sounded to them like a malapropism.

Take a look at the graphic. When we subitize the dots in the picture, we arrive at the correct answer without “having to think.” That’s a very different process from estimation or counting, as demonstrated by the experimental trials of Kaufmann, Lord, Reese, and Volkmann, and by the research that preceded their study. When a test subject estimated the number of dots in the picture, they were using characteristics other than what was immediately apparent to their subconscious; they were inferring their answer based on density of the dots, the shape they made, or any number of other observable principles. When they counted, of course, they were using a fully rational, conscious process to arrive at their answer. When they subitized (and here’s the critical point), they were fully validating the power of their subconscious, and the test results demonstrated the change: the answers were disproportionately faster, more accurate, and more confident when the test subjects could subitize. It turned out, as soon as the number of dots went 6 or lower, a different part of the brain went to work.

Today, subitizing is a recognized modality in several different pedagogical methods, including Montessori schooling and Zoltan Dienes’ theories for mathematics education. It’s also a central characteristic of the Boulanger-influenced Ploger method for musicianship, which I have studied for five years. In Prof. Ploger’s view, estimating is a poor substitute for subitizing, and counting is summarily pointless. She tells me faithfully, “If you can’t do it quickly, it’s irrelevant.” In other words, as soon as our work is dominated by our conscious mind, that work ceases to be fluent. Subitizing, conversely, is a “love-mode” response (another Ploger term). It’s as if our unconscious mind is telling us, “Of course it is. What’s next?” The unconscious loves to notice things, and it’s very, very good at it—but only when our conscious mind stays out of the way. “Love,” the saying goes, “is a harvest of attentions.” We’re going to explore manifestations of this love in the music that follows.

But let’s begin by imagining a room. The floorboards are honey-oak, carefully polished, and creak gently when they’re passed over by the two friends that enter. Mozart is humming a tune as he takes a seat on a cushion, leaning back against the wall with his legs splayed in front of him. Meanwhile, Jesus is relaxing cross-legged on his own cushion in another part of the room, while paying careful attention to the other man.

ADAGIO BEGINS AT 12: 48

Mozart, String Quintet no.3 inG Minor, k.516 I. Allegro - 00:00 II. Menuetto. Allegretto-Trio - 07:35 III. Adagio ma non troppo - 12:48 IV. Adagio-Allegro - 21:34 Amadeus Quartet & Cecil Aronowitz: Norbert Brainin, Siegmund Nissel, violins Peter Schidolf, Cecil Aronowitz, violas Martin Lovett, cello London, 1966

MOZART

Consider the lilies how they grow: they toil not, they spin not; and yet I say unto you, that Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. If then God so clothe the grass, which is to day in the field, and to morrow is cast into the oven; how much more will he clothe you, O ye of little faith? [Luke 12, KJV]

JESUS

And here the fellow in his kingly garb

Pours out a stream of someone else’s words.

Why dost thou thus proclaim thy love for me

In a language that’s outside thy native tongue?

MOZART

OK, sure, fair enough. Consider then,

My string quintet’s Adagio. Here, listen.

What we’ll come to understand is that Mozart was showing us things that were as obvious to him as a sonnet was to Petrarch, or a river was to Claude Lorrain. Though it might not seem this way, we’re going to look at the obvious.

Numbers will govern our looking. The numbers from 6, on down to 1, are the numbers our brain naturally subitizes. They’re instantaneously apparent when they confront us. When we think about it, of course the most blindingly obvious things that happen to us—in life, love, and music—must happen in sixes, fives, fours, and threes! We’ll use this unifying phenomenon to examine the bridges between our chosen repertoire.

(Why not twos, ones, and zero? The answer is a matter of substrates. It’s the same reason we won’t discuss the pervasive repercussions of figurenlehre—the library of atomic musical gestures that undergirds Western music from the early Baroque. The mechanics of this essay prohibit this particular magnifying glass. Everything we examine will be deliberately curated to show itself on the large scale and the smallest possible scale; but imagine, in a different field, analyzing a political race vis-a-vis the psychology of each American family, or each American voter, or each individual opinion of each American voter. As integral as all of these things are, using them as a substrate is analytically impossible. Likewise for overly tiny musical units. We shall toil not, nor shall we spin; rather we shall go on stating the blindingly obvious.)

Sixes: Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 6 in E minor, IV. Epilogue

EPILOGUE BEGINS AT 23:45

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra - Andrew Manze conductors at the Royal Albert Hall - London - BBC PROMS 2012. Presenter: Petroc Trelawny

In preparation to understand this epilogue, let’s open the box with a concept that predates Vaughan Williams by several centuries. The sonnet is a poetic form that presents a basic two-part “conflict/resolution” structure: the opening octave presents the conflict, and the closing sestet resolves it. Our ears are liable to perk up with the sestet, since it’s the more flexible of the two parts: while the 2 quatrains of the octave tend to stick to a stolid ABBA ABBA rhyme scheme (notice the last word of each line), the sestet varies widely. Why does this matter?

If we are resolving a conflict using poetic means, we need need need to answer it simultaneously using our words’ meaning (the content) and their structure (the form). The sestet carries a heavy responsibility! Perhaps that’s why it needs to be versatile. In response to the conflict ABBA ABBA, Petrarch structured his sestets CDE CDE (through-rhymed triplets) or CDC CDC (rhyming palindromes). Shakespeare addressed the conflict in a different way: he capitulated with EFEF GG (a quatrain plus a final couplet). Instead of defying the opening quatrains, he assimilated them!

Now consider, in addition to the lilies, the first 8 bars of Vaughan Williams’ epilogue. Here in the first violin part are six notes (F G Ab B C Eb), which we beautifully subitize as soon as we hear them. I discard E and Bb as “musica ficta,” necessary modulatory alterations, to the original motif’s key area. Thus, the first six pitches define our musical unit. So, how does our friend Ralph use his six notes? He uses their rhythmic symmetries to suggest a sonnet (see below):

Scorn not the Sonnet

Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic, you have frowned,

Mindless of its just honours; with this key

Shakespeare unlocked his heart; the melody

Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound;

A thousand times this pipe did Tasso sound;

With it Camöens soothed an exile's grief;

The Sonnet glittered a gay myrtle leaf

Amid the cypress with which Dante crowned

His visionary brow: a glow-worm lamp,

It cheered mild Spenser, called from Faery-land

To struggle through dark ways; and, when a damp

Fell round the path of Milton, in his hand

The Thing became a trumpet; whence he blew

Soul-animating strains—alas, too few!

Every half-measure (which we’ll call a “block”) equates to a line of English. Since the pitch content is limited to a single set (the six-note pitch set detailed above), we can allow ourselves the freedom to consider rhythm as our definitive content. Letting the rhythm be our guide, then, the “rhyme scheme” of our excerpt goes ABBB BCBA. Note the multiple symmetries:

Rhyme: blocks 1 & 8

Rhyme: blocks 3 & 4

Rhyme: blocks 5 & 7

Rhyme: block pairs 1-2 & 3-4

Alliteration: block pairs 5-6 & 7-8

Envelope: blocks 1-8. The imbalance of three “B” blocks in quatrain 1 are balanced by the “C” block in quatrain 2, and the final “A” block seals the palindromic structure. This proto-sonnet’s “conflict statement” is fully self-contained, and waiting for a resolution (remember this!).

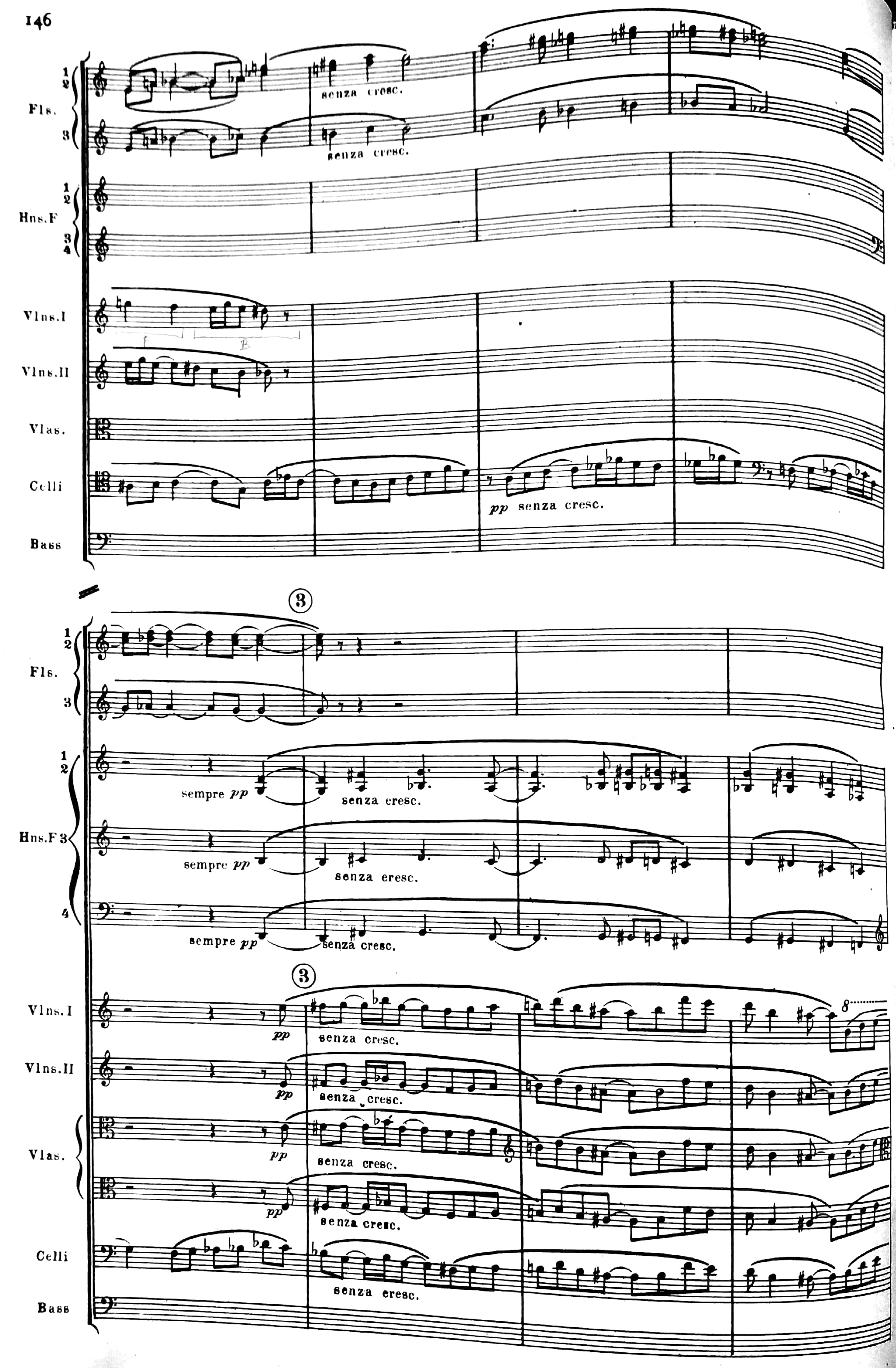

The suggestion is even stronger in another instance. See right (violin 1):

The rhyme scheme here is (A) BCAB BDEB DFB. Overlooking the quasi-anacrustic “A” block, the symmetries are even closer to standard sonnet form:

Envelope: blocks 1-4

Envelope: blocks 5-8

Rhyme: blocks 1, 4, 5, 8, 11

Envelope: blocks 1-11. The overarching symmetry runs through the two enveloped quatrains and ends on the final block.

(Interlude)

JESUS

You see, dear one, sonata form this ain’t.

But your sonatas carried on into

Most beautiful things.

MOZART

Yet can the same be true,

For sonnet and sonata, song and chant?

Can they display a unity of themes,

Economy of content, and besides,

Through sexy tones and sleek chromatic slides,

Afford me virtuous scandal, beds enseam’d?

JESUS

O, tempt me not, young libertine, but list.

I tell you what you seek is there ahead.

For Ralph Vaughan Williams’ sixth is a gentle nod

To those who came before. Dear friend, desist,

And see what scandals spring from your dear beds,

Along with things more fitting for your God.

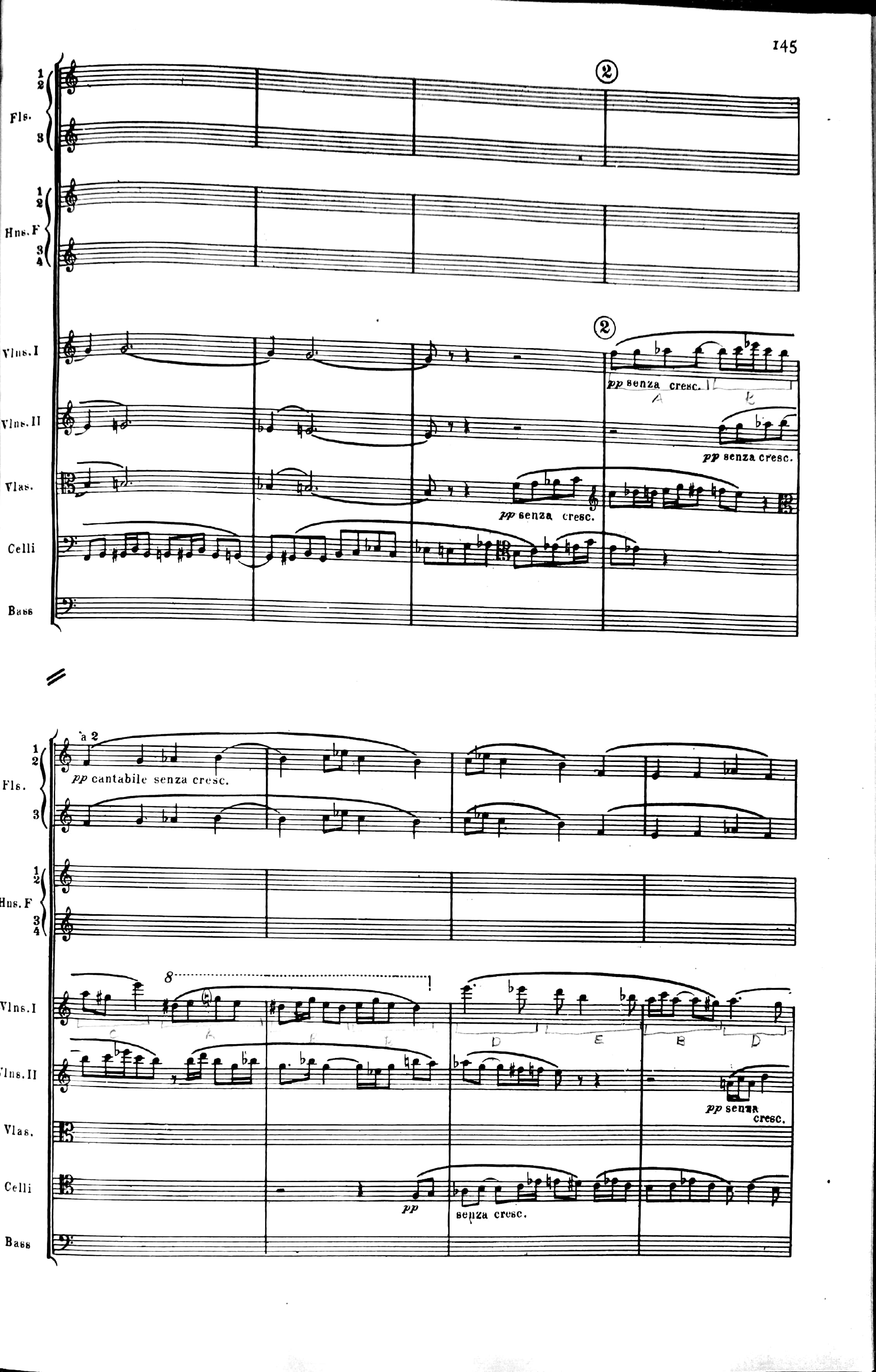

Fives: DOMINANT ASYMMETRY

Let’s revisit the final moments of Vaughan Williams’ Sixth Symphony (see video above), and observe the score below. Notice anything after the oboe solo?

There’s a sonnet-parallel we’ve missed, but this one has to do with fundamental asymmetries. Remember that the sonnet form is comprised of two quatrains and a sestet (a “trinity of forms,” if you like). Likewise, notice that two chords are in conflict in the upper strings: D# major and E minor. These comprise our functional “conflict statement.” But what happens in the “sestet motif” that could reconcile them? Now it is no longer six notes but five (Eb F G G# B). And, as if by coincidence, it is helpless to prevent the conflicting chords to spin on against one another. The motif wastes away into smaller and smaller truncations, and the chords spin on, conflict unresolved. The change from 6 pitches to 5 has suggested an asymmetry that undermines the closing of this piece. This suggested 5-unit asymmetry is fundamental to Western harmony. The V chord, inherently unstable and begging for tonic resolution, symbolizes both the faraway yearning and the homeward road.

I say with no little irony, Paul Nash demonstrates that he, too, has a finger on this pulse in “Dead Spring” (1929). So close that your eyes feel unfocused, Nash juxtaposes a limp cluster of dead leaves with a host of inanimate setpiece figures. The leaves’ lines show more life than the figures ever could, and yet here again, form battles with content. The leaves are officially “dead,” but nonetheless curl and flex in the center of the frame, a formal suggestion of life. The setpiece figures’ suggestions of triangular trinity and rectilinear duality give us a clear and lively implication of the number five—further highlighting the inherent asymmetries. “Five” appears to be the sonnet’s undoing, and artists across genres fight to contend with it.

JESUS

You knew this too, Wolfgangus, didn’t you?

Your urmotiv at first expanding, thus,

From trichord to triad, a 5-note span.

The instability, the eros blind,

All part o’ your plan.

MOZART

Of course it is. What’s next?

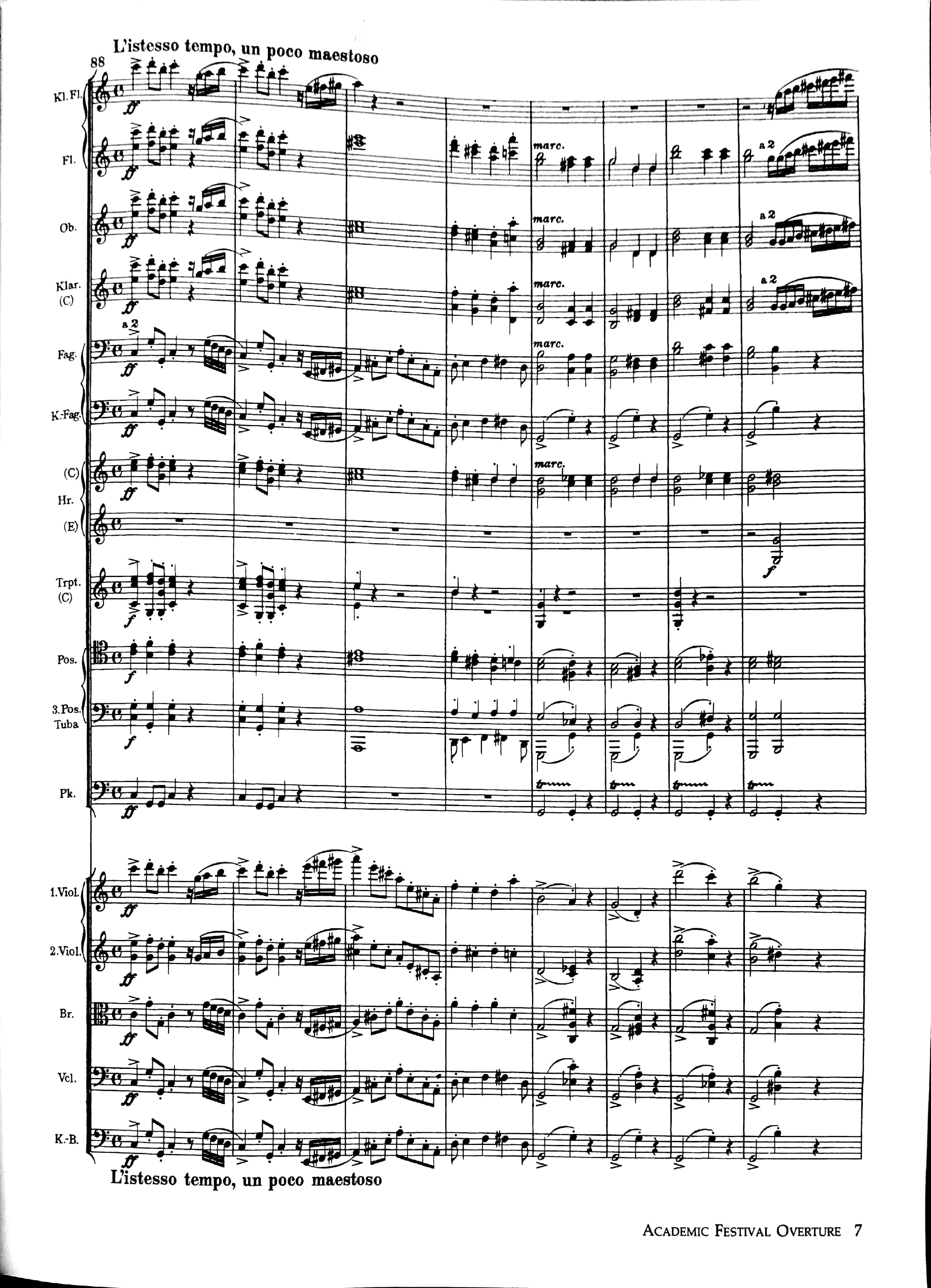

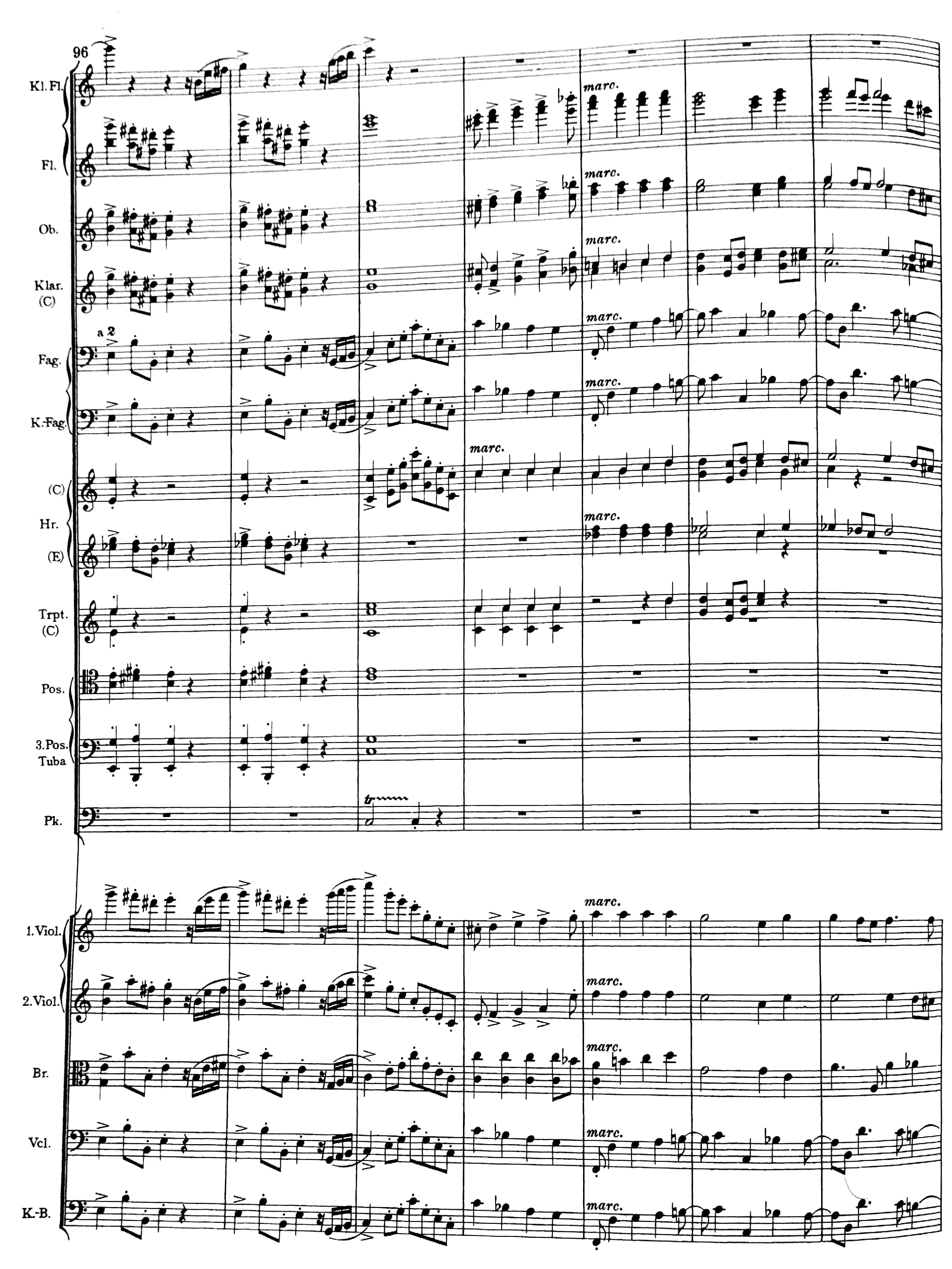

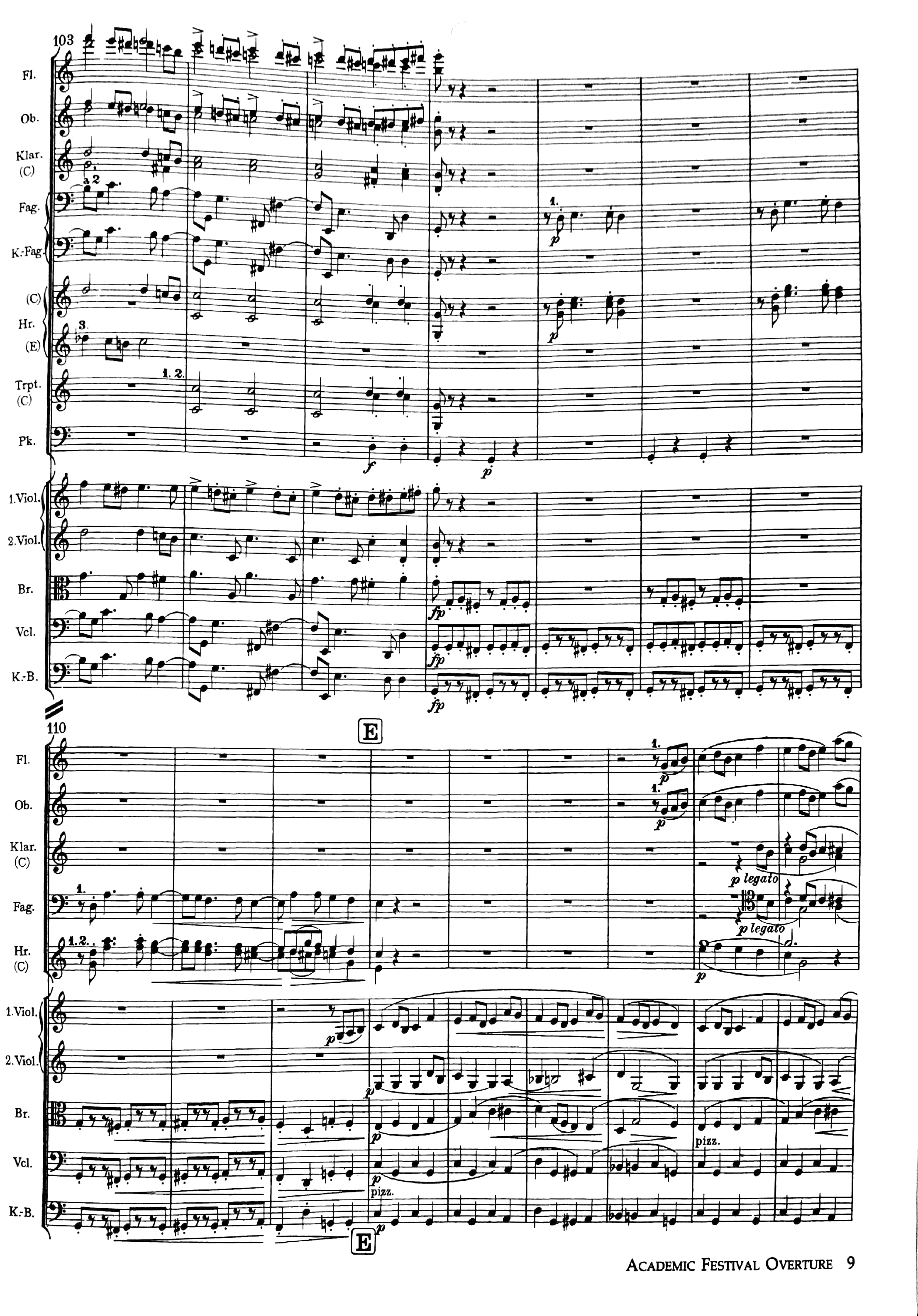

Brahms, in fact, is next. His Academic Festival Overture is a search for symmetry within a sprawling medley of song. The excerpt here is a prime example of this search frustrated by dominant function. C major (m. 88) drops a major third to A major, then a second to G major, the dominant. So far so good, but will Brahms be able to symmetrize? He begins again, promisingly, in E minor (m. 96, a diatonic iii), a major third above C. But instead of filling in F major for the full symmetry (a tempting diatonic IV, no less!) he repeats the major-third drop, this time to C major, and then trips bizarrely through Bb to D and G, landing on his butt back on the tonic C. Hindsight is 20/20, so we know that E minor could only have been a deceptive cadence that needed the secondary dominant D major to set it to rights. Still, the effect is squirmy. What Brahms does more comfortably in Academic Festival Overture is inhabit the realm of fours.

Mozart Quintet G minor K. 516, m. 23

Fours: TETRACHORDS

Is it any surprise that a student of Michael Alec Rose would expound on the tetrachord? Before we dive, however, let’s open with Brahms’ own opening.

From the very first figure, we spy fours at work. The first violins have a power-packed first two bars: a four-note neighbor tone figure followed by a descending minor tetrachord. Opening bars like these offer nearly infinite versatility in the tonal sphere. Brahms, the ironic academic, takes the technical path of least resistance. No tonal shenanigans, no points of imitation, just a repetition in the dominant. Is he already jesting at the fact that he will never quite contend with dominant asymmetry? Maybe. After all, right under our nose, the first two statements are 3-bar phrases! It seems that there’s self-conscious asymmetry even in Brahms’ squarest motivic statements.

Brahms, Academic Festival Overture

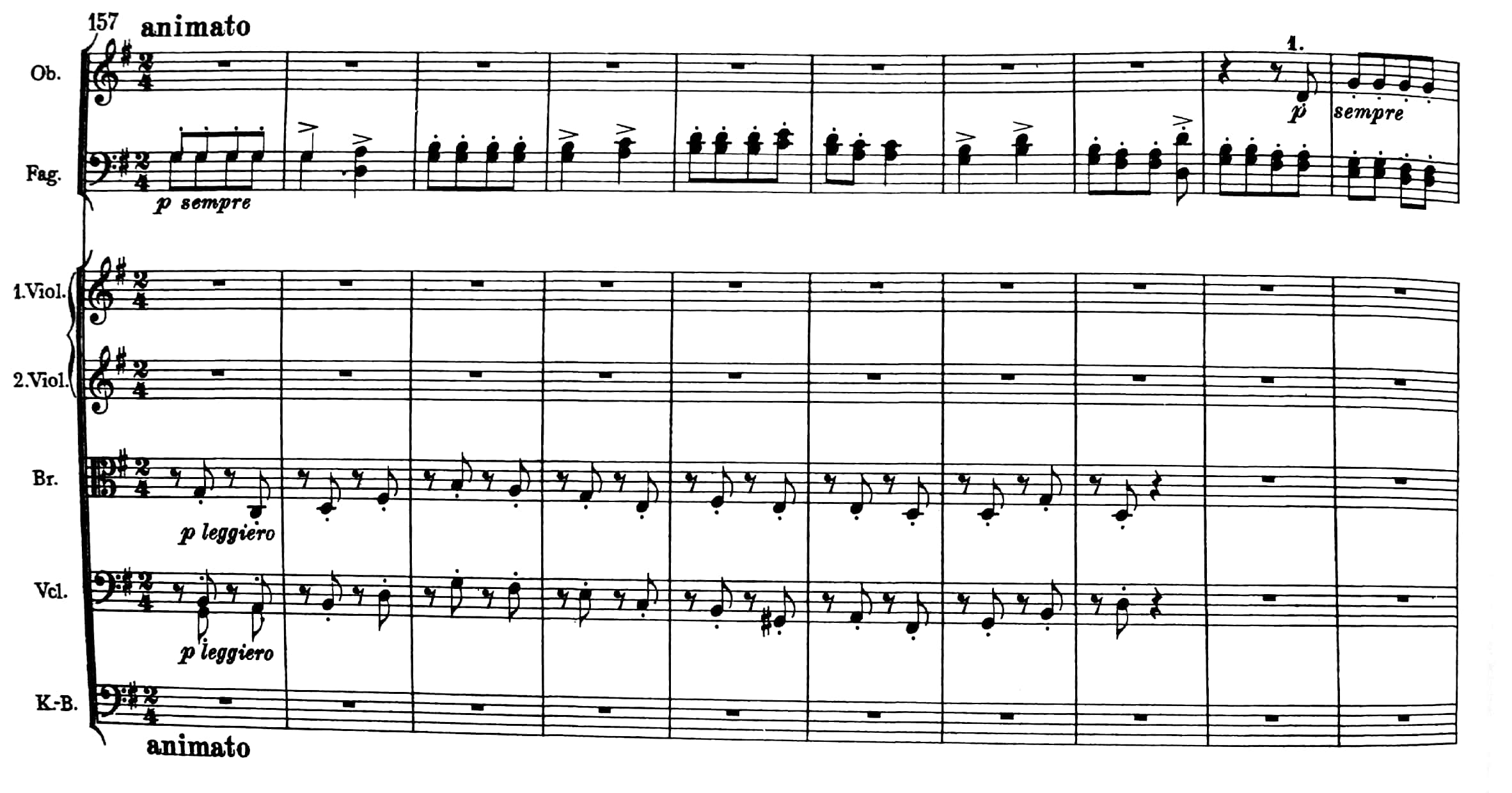

Just for another synechdochal example, take the cutesy bassoon solo at m. 157. What could be more foursquare than a march? Until, that is, Brahms, adds an extra bar at the end (m. 165), just before the oboe’s point of imitation. If asymmetry’s built into harmony, Brahms thinks to himself, then, well, form must reflect content—an extra bar it is. And just like any principle in this composer’s oeuvre, it’s utterly pervasive in the Overture, in ways that this lecture will not address.

Know what else features a descending tetrachord? Our Mozart piece, at last. Our excerpt begins at 12:48.

MOZART

Consider my Adagio, forthwith:

Five players and their slice of your Creation.

The second bar alone does give us good:

A tetrachord, with ornaments, descending

From B flat (dominant) to F below.

JESUS

Then, following the downward rush of [measure] 4,

Your chromatism brings it home in [measure] 7.

MOZART

How could I let it pass? Ascent, descent,

The eros and the pathos and the ludus

Descending tetrachords are but a foretaste.

Let’s onwards to the secondary themes

[measure 18 & 27, and their recapitulatory counterparts],

Descending all the way to tiptoe dancing

Upon the dominant in 32.

Then onward further to Transition Two,

And though it’s in the dominant right here,

In 72 it’ll soon be set to rights.

Here’s the best of our sonata-form:

Like chambered locks the potencies give way,

Until all tensions, sated, dissolve away.

JESUS

But, Mozart, with respect, a tetrachord

Was not the reason this work came to be.

That honor goes to holy number three.

Threes: Divine Flows

MOZART

Do note the grain we ground last Passover,

See how it swells itself upon our table:

Embodied now, the grain’s itself the bread.

JESUS

Likewise a trichord, ascending and descending:

The highest and the lowest changing voices,

This theme embodies your Adagio. [m. 1]

MOZART

Now track my trichord as you’ve tracked your nation.

JESUS

Writ large is your motif’s harmonic motion;

The first two beats [m. 1] encompass all the rest:

One tonic [m. 1], then one dominant [m. 17], then tonic [m. 37].

MOZART

My work is as a rocky seamed face,

Consistent by its very nature, formed

Most carefully, yet all inev’table.

Thus, see the very trichord thrice again,

As upward motion, sol la si [m. 1-2], and then

Truncation in bar 3, first violin,

And languorous elongation in bar 4.

See one seam here [m. 5], a cambiata theme

That frustrates th’ forming trichord with a leap

That seals it tighter for its dissonance.

JESUS

So likewise does a wound that healeth skin

Plain-bind it tighter, even after silence. [m.10]

The break in sound is no longer betrayal

When cambiata’d trichords reemerge [m. 11]

In counterpoint orchestrally prepared. [m. 5-10]

MOZART

And then, Transition One, we have our first

Bedazzling instance: triad as trichord,

Here [m. 17], see this sev’n diminished 6 of V.

The instability, the eros blind.

JESUS

And every descending line, from here

Through Exposition and the sewn-in Recap,

Is true rendition and remembrance fond

Of trichord, trichord, trichord?

MOZART

Verily!

JESUS

But where, oh, does it end?

MOZART

It’s infinite.

My urmotiv expands to fill a canyon, [Coda, m. 76]

And shrinks to fit a thimble, [chromatic descent, m. 37] if I ask.

It’s elemental, just like Claude Lorrain’s

Good study of a stream.

JESUS

Its levels three,

The first far ‘way above our heads, and then,

The second before our feet, and then the third,

A stone’s throw to the right. Your urmotiv

Is plain to see.

MOZART

And water washes still, in motion contr’y

As if it were a pair, violin and cello,

In measure 1 of my Adagio.

Adagio indeed these waters flow,

And eddying, ebbing, falling, never standing

Not for a moment’s rest, like time’s swift flow.

So easily it goes, while I’m at ease.

JESUS

If immortality you seek, go find

Some antic Roman who’ll remember you.

But try instead to see the unity

Your fertile mind has conjured while at work.

For God did grant you not a perfect life,

But a perfect road, and travel it you must.

For see the end that you yourself created.

MOZART

Sure, final vindication long-awaited: [m. 78]

Scar-tissue cambiata healing brings,

Behaving as a tree’s rich cambium

A “secondary thickening” that binds

Each measure in an anacrustic turn;

The final bars full bound together thus,

The trichord realized as healing salve.

JESUS

And all creation bound together thus,

The singularity from whence it came.

I6/4 to I: see, one, two, three! [m. 78-80]

Then I to V4/3: see, one, two, three! [m. 80-81]

Then I, I, I. A trinity divine,

Thrice witnessed, so, my brother, you are mine.

Drawing Games with My Cousins

I shared last Christmastime with my family--a dear blessing. I made these drawings together with my two brilliantly talented younger cousins: M. is a champion athlete, and S. is a dancer born to a dance-healer. Both my cousins are strong, beautiful, and beloved.

[Untitled, Rama + M. + S., pen and ink]

[Untitled, Rama + M., pen/mechanical pencil]

[Untitled, Rama + M., pencil/watercolor]

A Little Digest of "Dangerous Ideas"

A small exhibition from my personal journal. I’d love to talk about any one of these: message me.

The lion’s share of credit goes to Carl Smith and Michael Alec Rose, my mentors.

To amuse a friend in orchestra rehearsal. After W. A. Mozart & Greg Pattillo. See here for more.

Program Notes for Recital 10/26/16

Program Notes

(All additional listening, for the brave and curious, is available on YouTube)

Bachianas Brasileiras No. 6 for flute and bassoon (1938)

This tricky little vignette was written by the Rio-born, Paris-trained Heitor Villa-Lobos. He’s known for lovely, idiomatic guitar preludes, but this “Brazil-Homage to Bach,” on the other hand, features two instruments that make very odd bedfellows. The first movement (Aria - Chôro) begins with a twirling flute figure, languidly descending to meet the passionate voice of the bassoon. The instruments engage in counterpoint, weaving harmonically tighter and tighter until they finally settle in unison on a low D. The second movement (Fantasia) is verily a flight of fancy. It plants a flag with the quintessentially Latin 3+2+2 rhythmic idea, introduces bel canto secondary themes, and then returns to variations, cadenza, counterpoint, and the conclusive final dash.

Additional listening: Liebermann Trio (Evelyn Mo, Oliver Herbert, Rama Kumaran - 2015)

Concerto No. 7 in E minor for Flute and Orchestra (1787)

We begin our French excursion with this delightful Classical-era concerto, published the same year as the US Constitution! The small chamber orchestra will be conducted by the soloist. Francois Devienne was a flute professor at the Paris Conservatory of Music, and he composed this concerto so expertly that the melodies are totally natural to the instrument—they practically play themselves (and are undeniably pretty). This lush concerto was revived by Jean-Pierre Rampal in the 1960’s, but it still isn’t played as often as the more popular Mozart Flute Concerto in G Major (published 9 years earlier).

Here you’ll see an eighteenth-century convention that’s almost abandoned in modern performance practice: the improvised cadenza. The two solo cadenzas in the second movement will be improvised extempore, making the performance you witness tonight quite literally one-of-a-kind. It will never be played the same way again!

Additional listening: Mozart Flute Concerto in G (Jean-Pierre Rampal, Zubin Mehta - 1989)

Le Merle Noir (1952)

Here we escape 18th-century France into a very different 20th-century France, a country still recovering from World War II. Olivier Messiaen wrote this piece as a test for competitors in the annual flute competition at the Paris Conservatory of Music, where he was (just like Devienne) a professor. Messiaen was deeply religious, and his music reflects his reverence. He was also fascinated by birdsong! “Le Merle Noir” (“The Blackbird”) is his first piece dealing with one specific species of bird, and it uses complicated atonal melodies to transform the sound of a flute into the sound of this bird.

The realism of Messiaen’s literal notation is in shocking contrast to the artifice of its large-scale structure: in one of the oldest formal tricks in the book, Messiaen uses a canon to develop his material. He frames this central canon with two other elements: a cadenza (a densely notated, unmetered selection of birdcall fragments) and a vif (a lively dance interposing a 12-tone piano part into a sudden flurry of activity from the flute). This whole structure (cadenza, canon, vif) is repeated twice, giving the piece a recognizable structure. We can hold on to this structure in the midst of atonal wanderings and strange sounds.

Additional listening: Messiaen Quartet for the End of Time, III. Abyss of Birds (Paul Meyer - 2000)

Sonata “La Vibray” (1732)

Almost all of Blavet’s Opus 2 flute sonatas are named after places; Vibraye is a town in northern France. But this piece is at the end of the program for a different reason altogether: it’s a challenge, a call to action, a Rhetorical piece. It’s just like a speech: every note has a meaning--upward lifts, downward sighs, joyful ornaments and somber ones too. In the Eloquent style of the 17th and 18th centuries, Michel Blavet invites performers to join him in the art of musical “oratory,” using his “words” (the notes on the page) and inflect them with meter, ornament, and affect. These are what Michael Rose calls audible signs and they live in our imagination, waiting to be animated. Carl Smith and Jed Wentz are both experts in these audible signs, and their work serves as a guide and inspiration for this performance.

Additional listening: Telemann Suite in A minor (Hanspeter Oggier, Ensemble Fratres - 2017)

Acknowledgments

Amma and Appa, for everything.

Prof. Leslie Fagan, for her helpful, surefooted guidance and support.

Destin Tunca, Amy Thompson, Ben Harris, and many others, for friendship and inspiration.

Profs. Michael Rose, Carl Smith, Peter Kolkay, and Stan Link, for a valuable education in progress.

Polly Brecht, Andrew Sledge, Yani Quemado and the orchestra, for the skill, energy, and imagination you’ve dedicated to this program.

Lovina Botts, Karen Hansen, and Tracy Harris (my flute teachers before college), for bringing me here.

My students back home in Hemet.

Everyone watching the livestream—special shoutout to the Harvard Street Music Exchange!

My studio-mates at Blair, and the musical community here and far beyond.

Professor Dikeman in memory.

Soli Deo Gloria.

Mineral Veins?

I took a first listen to Fleet Foxes' new album "Crack-Up" while making this drawing.

Started with a framing layer of graphite pencil. After I placed the central figure, I started sketching within the streaks of pencil shading. Reinforced the lines with pen & ink, tried out getting a mineral iridescence with colored pencils, and darkened the "obsidian" with a permanent marker.

The result was something rocky.

Illustrated Score Part 2

I asked a dear friend while I worked on the project, "In a piece of art, would you rather choose cleverness or sincerity?" She didn't think twice: "Sincerity." Her choice validated the choices and sacrifices I'd made, and all the choices/sacrifices I would make before the project was finished.

I could have leveraged history and popular culture to make my drawings ironic. But Ligeti once said, "I am in a prison: one wall is the avant-garde, the other wall is the past, and I want to escape." It would have been fashionably cruel to make wry sport of his earnest work. I might care for fashion, but certainly not for cruelty.

So--voice-leading lead-ropes converging, multiplying, and splicing back together. An em dash responds to the exclamation mark on the previous panel. The narrative continues below, an undercurrent.

Panel 6/13

Panel 7: the green/pink symbols become monograms. Meanwhile, the seeds settle.

Panel 7/13

Panel 8: punctuated symbols, as the electric roots intensify the action

Panel 8/13

Panel 9/13: climax. Big blue pine from blue seeds, purple cactus creature, brown cattails, and those little curly reddies. Overhead swirls a benevolent streak of green/pink.

Panel 9/13

Panel 10: A dry spell. The green/pink swirl flattens, then flatlines. The (active) narrative doesn't address this "coda".

Panel 10/13

Panel 11/13

Panel 12/13

Silence until--the rain begins.

Panel 13 of 13

Illustrated Score Part 1: G. Ligeti Viola Sonata, VI. Chaconne chromatique

Late in 2016, violist Han Dewan invited me to join five other artists illustrating the score of the Viola Sonata of György Ligeti. Han texted me a very quotable tidbit the other day, describing the piece:

"I love the sixth movement especially. There's something ancient about the sound even though it's unmistakably new."

Han is a violist currently completing her undergraduate degree at the Blair School of Music in Vanderbilt University. This project contributed to her senior viola degree recital, to be performed on January 29, 2017. A livestream is available here. [EDIT: The panels will be live-projected onto a screen behind Han as she plays.]

I began experimenting on the first page, overlaying motif upon motif. Really, I was assembling my palette of elements. Lots of ideas...not nearly enough time and space to give each one room to grow. These were the tryouts. (College rewards the clever, so, since I'm a tried-and-true Vandy student, I began with self-irony. Pencil sketching just lends itself to wryness...)

Panel 1 of 13

Right at the outset, the project took a standstill. By testing out my range of possibilities, I had overcrowded the first page. I couldn't develop all these things at once, given my timeframe and the paper's physical real estate.

Plus, I wanted to turn right away from irony and cleverness. I'd rather be true to Ligeti's piece, Han's work, and the circumstances of this project's creation. A common thread in progressive spheres is "art with a conscience", so, paying my dues to modernist ethics, I started razoring away the dis-ingenuous-ness.

Panel 2/13

Page 2: I forbade myself from breaking the fourth wall. But the Blair School of Music peered in everywhere. Wall sconces and viol shapes and references to Musicianship I.

Those green and pink figures will soon take on a representative life of their own, deputizing for the music.

Panel 3/13

The third page introduced the second--and last--developing motif. My pencil technique is pretty limited, and plants are cute, small, and self-contained. They also tell a story. (See previous post "Experimenting with Gravity" for my best example of plant modeling.)

So, just for the analyzers, our cast of characters is this:

- Color-pencil abstractions, green and pink figures busily "translating" the piece in real-time. This element is reactive--I let the symbols respond to the music's behavior. The language changes with every panel (monograms, voice-lead-ropes, flatlines, and others).

- Plant and seed patterns, sketched in pencil and pen/ink, a narrative. This element is active--it imposes a story upon the music. The language stays the same.

Panel 4/13

Part 2 to be published on Sunday, Jan 29.

Panel 5/13

Experimenting with Gravity

A reference point for "Illustrated Score": modeling plant textures and shapes

Originally published on Facebook - August 25, 2016

Deskwork - Flexing Muscles

The mundanity of my desk was a backdrop. I was toying with some words,

"Take a curve and turn it into a shade."

Which, quite pristinely, became a drawing prompt. I came up with a few more.

Experimenting with Pointillism - Peacock

I needed to expend some focused effort. Resorted to a favorite diversion, texturing with my fountain pen.

10 Questions with Rama Kumaran

Meet Rama Kumaran, a sophomore who was the winner of the National Flute Association’s Young Artist Competition this summer and was featured on National Public Radio’s “From the Top” series at age 16. He talks Harry Potter fan fiction, his strategies to connect with an audience and what drew him to his flute in the first place. He dives into the psychology of musical performance, and considers, with great honesty, the stress of his craft.

Read moreOn Performing (The Flute Examiner) →

“I am prepared, I am capable, and I am worthy of my audience. I recognize the honor, the privilege, and the blessing to be able to transform my listeners with every moment I present myself before them.”

Read moreThe Incredible Power of Art →

Right now, I have no idea what you’re thinking. But do me a favor: take a second and look inside your own head. What are you FEELING right now?

Read more

![[Untitled, Rama + M. + S., pen and ink]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55d1456ee4b08cb2994fd315/1550474596069-NHY0F5CSUGZ3KIEHPYU2/upload.jpg)

![[Untitled, Rama + M., pen/mechanical pencil]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55d1456ee4b08cb2994fd315/1550474614940-6L0GEWKXIBZ492GBJN39/upload.jpg)

![[Untitled, Rama + M., pencil/watercolor]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55d1456ee4b08cb2994fd315/1550474631411-AAO46H7MSNEDPMEZAYL2/upload.jpg)