Introduction: Subitizing

https://blog.wolfram.com/data/uploads/2011/05/subitize.gif

There’s an article published back in the mid-20th century coining a new word, “subitize.” Breaking it down, the word’s first root is the Latin verb subitare (“to arrive suddenly”). That word gave us the musical marking subito, i.e. subito presto, “suddenly quick” (when we’re jolted out of a lull). The second root, -ize, is Greek. This is because, as the authors confessed, the corresponding Latin suffix sounded wrong. “Subitate,” an all-Latin word, was too close to too many other English words; it sounded to them like a malapropism.

Take a look at the graphic. When we subitize the dots in the picture, we arrive at the correct answer without “having to think.” That’s a very different process from estimation or counting, as demonstrated by the experimental trials of Kaufmann, Lord, Reese, and Volkmann, and by the research that preceded their study. When a test subject estimated the number of dots in the picture, they were using characteristics other than what was immediately apparent to their subconscious; they were inferring their answer based on density of the dots, the shape they made, or any number of other observable principles. When they counted, of course, they were using a fully rational, conscious process to arrive at their answer. When they subitized (and here’s the critical point), they were fully validating the power of their subconscious, and the test results demonstrated the change: the answers were disproportionately faster, more accurate, and more confident when the test subjects could subitize. It turned out, as soon as the number of dots went 6 or lower, a different part of the brain went to work.

Today, subitizing is a recognized modality in several different pedagogical methods, including Montessori schooling and Zoltan Dienes’ theories for mathematics education. It’s also a central characteristic of the Boulanger-influenced Ploger method for musicianship, which I have studied for five years. In Prof. Ploger’s view, estimating is a poor substitute for subitizing, and counting is summarily pointless. She tells me faithfully, “If you can’t do it quickly, it’s irrelevant.” In other words, as soon as our work is dominated by our conscious mind, that work ceases to be fluent. Subitizing, conversely, is a “love-mode” response (another Ploger term). It’s as if our unconscious mind is telling us, “Of course it is. What’s next?” The unconscious loves to notice things, and it’s very, very good at it—but only when our conscious mind stays out of the way. “Love,” the saying goes, “is a harvest of attentions.” We’re going to explore manifestations of this love in the music that follows.

But let’s begin by imagining a room. The floorboards are honey-oak, carefully polished, and creak gently when they’re passed over by the two friends that enter. Mozart is humming a tune as he takes a seat on a cushion, leaning back against the wall with his legs splayed in front of him. Meanwhile, Jesus is relaxing cross-legged on his own cushion in another part of the room, while paying careful attention to the other man.

ADAGIO BEGINS AT 12: 48

Mozart, String Quintet no.3 inG Minor, k.516 I. Allegro - 00:00 II. Menuetto. Allegretto-Trio - 07:35 III. Adagio ma non troppo - 12:48 IV. Adagio-Allegro - 21:34 Amadeus Quartet & Cecil Aronowitz: Norbert Brainin, Siegmund Nissel, violins Peter Schidolf, Cecil Aronowitz, violas Martin Lovett, cello London, 1966

MOZART

Consider the lilies how they grow: they toil not, they spin not; and yet I say unto you, that Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. If then God so clothe the grass, which is to day in the field, and to morrow is cast into the oven; how much more will he clothe you, O ye of little faith? [Luke 12, KJV]

JESUS

And here the fellow in his kingly garb

Pours out a stream of someone else’s words.

Why dost thou thus proclaim thy love for me

In a language that’s outside thy native tongue?

MOZART

OK, sure, fair enough. Consider then,

My string quintet’s Adagio. Here, listen.

What we’ll come to understand is that Mozart was showing us things that were as obvious to him as a sonnet was to Petrarch, or a river was to Claude Lorrain. Though it might not seem this way, we’re going to look at the obvious.

Numbers will govern our looking. The numbers from 6, on down to 1, are the numbers our brain naturally subitizes. They’re instantaneously apparent when they confront us. When we think about it, of course the most blindingly obvious things that happen to us—in life, love, and music—must happen in sixes, fives, fours, and threes! We’ll use this unifying phenomenon to examine the bridges between our chosen repertoire.

(Why not twos, ones, and zero? The answer is a matter of substrates. It’s the same reason we won’t discuss the pervasive repercussions of figurenlehre—the library of atomic musical gestures that undergirds Western music from the early Baroque. The mechanics of this essay prohibit this particular magnifying glass. Everything we examine will be deliberately curated to show itself on the large scale and the smallest possible scale; but imagine, in a different field, analyzing a political race vis-a-vis the psychology of each American family, or each American voter, or each individual opinion of each American voter. As integral as all of these things are, using them as a substrate is analytically impossible. Likewise for overly tiny musical units. We shall toil not, nor shall we spin; rather we shall go on stating the blindingly obvious.)

Sixes: Vaughan Williams Symphony No. 6 in E minor, IV. Epilogue

EPILOGUE BEGINS AT 23:45

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra - Andrew Manze conductors at the Royal Albert Hall - London - BBC PROMS 2012. Presenter: Petroc Trelawny

In preparation to understand this epilogue, let’s open the box with a concept that predates Vaughan Williams by several centuries. The sonnet is a poetic form that presents a basic two-part “conflict/resolution” structure: the opening octave presents the conflict, and the closing sestet resolves it. Our ears are liable to perk up with the sestet, since it’s the more flexible of the two parts: while the 2 quatrains of the octave tend to stick to a stolid ABBA ABBA rhyme scheme (notice the last word of each line), the sestet varies widely. Why does this matter?

If we are resolving a conflict using poetic means, we need need need to answer it simultaneously using our words’ meaning (the content) and their structure (the form). The sestet carries a heavy responsibility! Perhaps that’s why it needs to be versatile. In response to the conflict ABBA ABBA, Petrarch structured his sestets CDE CDE (through-rhymed triplets) or CDC CDC (rhyming palindromes). Shakespeare addressed the conflict in a different way: he capitulated with EFEF GG (a quatrain plus a final couplet). Instead of defying the opening quatrains, he assimilated them!

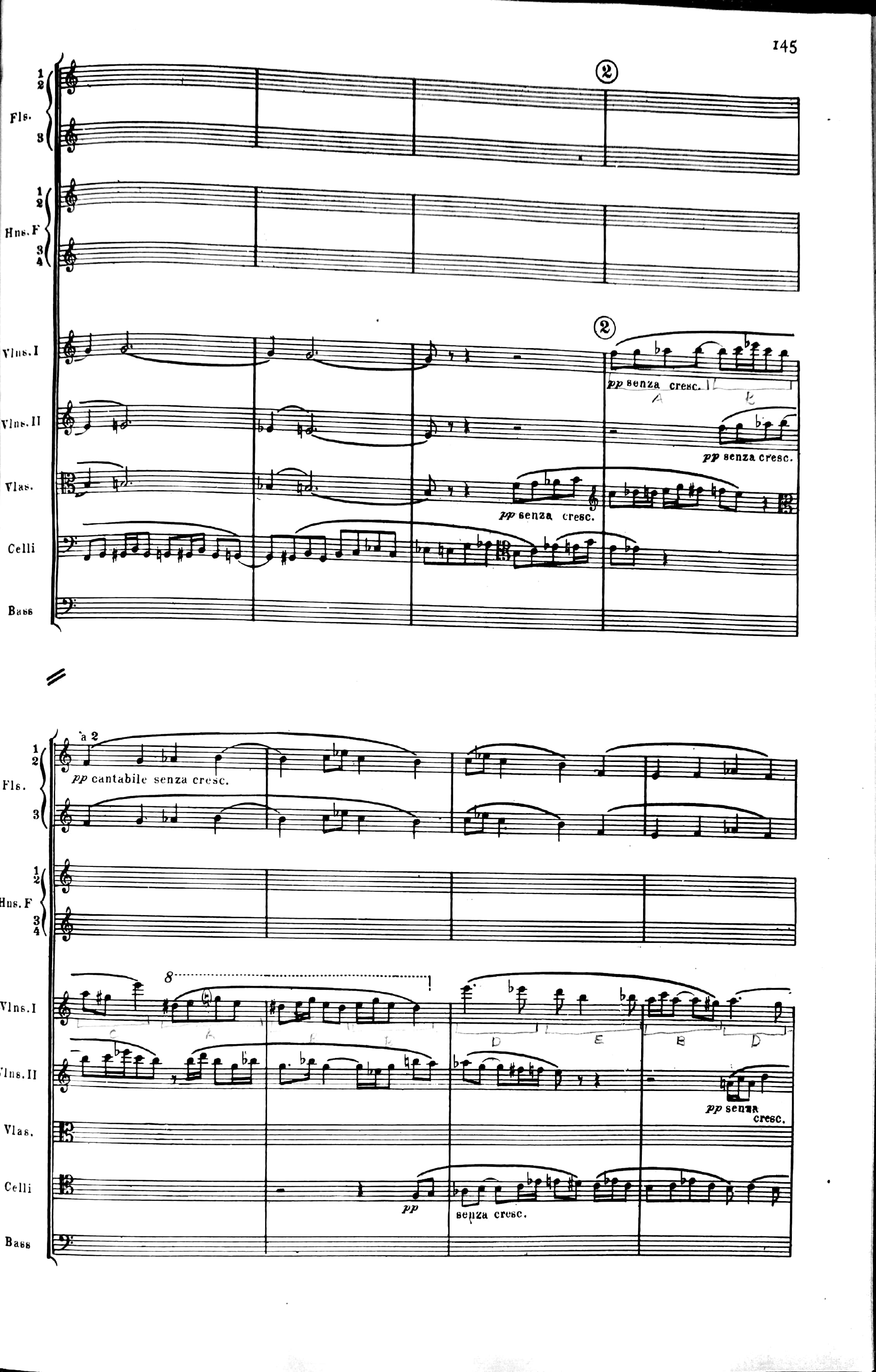

Now consider, in addition to the lilies, the first 8 bars of Vaughan Williams’ epilogue. Here in the first violin part are six notes (F G Ab B C Eb), which we beautifully subitize as soon as we hear them. I discard E and Bb as “musica ficta,” necessary modulatory alterations, to the original motif’s key area. Thus, the first six pitches define our musical unit. So, how does our friend Ralph use his six notes? He uses their rhythmic symmetries to suggest a sonnet (see below):

Scorn not the Sonnet

Scorn not the Sonnet; Critic, you have frowned,

Mindless of its just honours; with this key

Shakespeare unlocked his heart; the melody

Of this small lute gave ease to Petrarch's wound;

A thousand times this pipe did Tasso sound;

With it Camöens soothed an exile's grief;

The Sonnet glittered a gay myrtle leaf

Amid the cypress with which Dante crowned

His visionary brow: a glow-worm lamp,

It cheered mild Spenser, called from Faery-land

To struggle through dark ways; and, when a damp

Fell round the path of Milton, in his hand

The Thing became a trumpet; whence he blew

Soul-animating strains—alas, too few!

Every half-measure (which we’ll call a “block”) equates to a line of English. Since the pitch content is limited to a single set (the six-note pitch set detailed above), we can allow ourselves the freedom to consider rhythm as our definitive content. Letting the rhythm be our guide, then, the “rhyme scheme” of our excerpt goes ABBB BCBA. Note the multiple symmetries:

Rhyme: blocks 1 & 8

Rhyme: blocks 3 & 4

Rhyme: blocks 5 & 7

Rhyme: block pairs 1-2 & 3-4

Alliteration: block pairs 5-6 & 7-8

Envelope: blocks 1-8. The imbalance of three “B” blocks in quatrain 1 are balanced by the “C” block in quatrain 2, and the final “A” block seals the palindromic structure. This proto-sonnet’s “conflict statement” is fully self-contained, and waiting for a resolution (remember this!).

The suggestion is even stronger in another instance. See right (violin 1):

The rhyme scheme here is (A) BCAB BDEB DFB. Overlooking the quasi-anacrustic “A” block, the symmetries are even closer to standard sonnet form:

Envelope: blocks 1-4

Envelope: blocks 5-8

Rhyme: blocks 1, 4, 5, 8, 11

Envelope: blocks 1-11. The overarching symmetry runs through the two enveloped quatrains and ends on the final block.

(Interlude)

JESUS

You see, dear one, sonata form this ain’t.

But your sonatas carried on into

Most beautiful things.

MOZART

Yet can the same be true,

For sonnet and sonata, song and chant?

Can they display a unity of themes,

Economy of content, and besides,

Through sexy tones and sleek chromatic slides,

Afford me virtuous scandal, beds enseam’d?

JESUS

O, tempt me not, young libertine, but list.

I tell you what you seek is there ahead.

For Ralph Vaughan Williams’ sixth is a gentle nod

To those who came before. Dear friend, desist,

And see what scandals spring from your dear beds,

Along with things more fitting for your God.

Fives: DOMINANT ASYMMETRY

Let’s revisit the final moments of Vaughan Williams’ Sixth Symphony (see video above), and observe the score below. Notice anything after the oboe solo?

There’s a sonnet-parallel we’ve missed, but this one has to do with fundamental asymmetries. Remember that the sonnet form is comprised of two quatrains and a sestet (a “trinity of forms,” if you like). Likewise, notice that two chords are in conflict in the upper strings: D# major and E minor. These comprise our functional “conflict statement.” But what happens in the “sestet motif” that could reconcile them? Now it is no longer six notes but five (Eb F G G# B). And, as if by coincidence, it is helpless to prevent the conflicting chords to spin on against one another. The motif wastes away into smaller and smaller truncations, and the chords spin on, conflict unresolved. The change from 6 pitches to 5 has suggested an asymmetry that undermines the closing of this piece. This suggested 5-unit asymmetry is fundamental to Western harmony. The V chord, inherently unstable and begging for tonic resolution, symbolizes both the faraway yearning and the homeward road.

I say with no little irony, Paul Nash demonstrates that he, too, has a finger on this pulse in “Dead Spring” (1929). So close that your eyes feel unfocused, Nash juxtaposes a limp cluster of dead leaves with a host of inanimate setpiece figures. The leaves’ lines show more life than the figures ever could, and yet here again, form battles with content. The leaves are officially “dead,” but nonetheless curl and flex in the center of the frame, a formal suggestion of life. The setpiece figures’ suggestions of triangular trinity and rectilinear duality give us a clear and lively implication of the number five—further highlighting the inherent asymmetries. “Five” appears to be the sonnet’s undoing, and artists across genres fight to contend with it.

JESUS

You knew this too, Wolfgangus, didn’t you?

Your urmotiv at first expanding, thus,

From trichord to triad, a 5-note span.

The instability, the eros blind,

All part o’ your plan.

MOZART

Of course it is. What’s next?

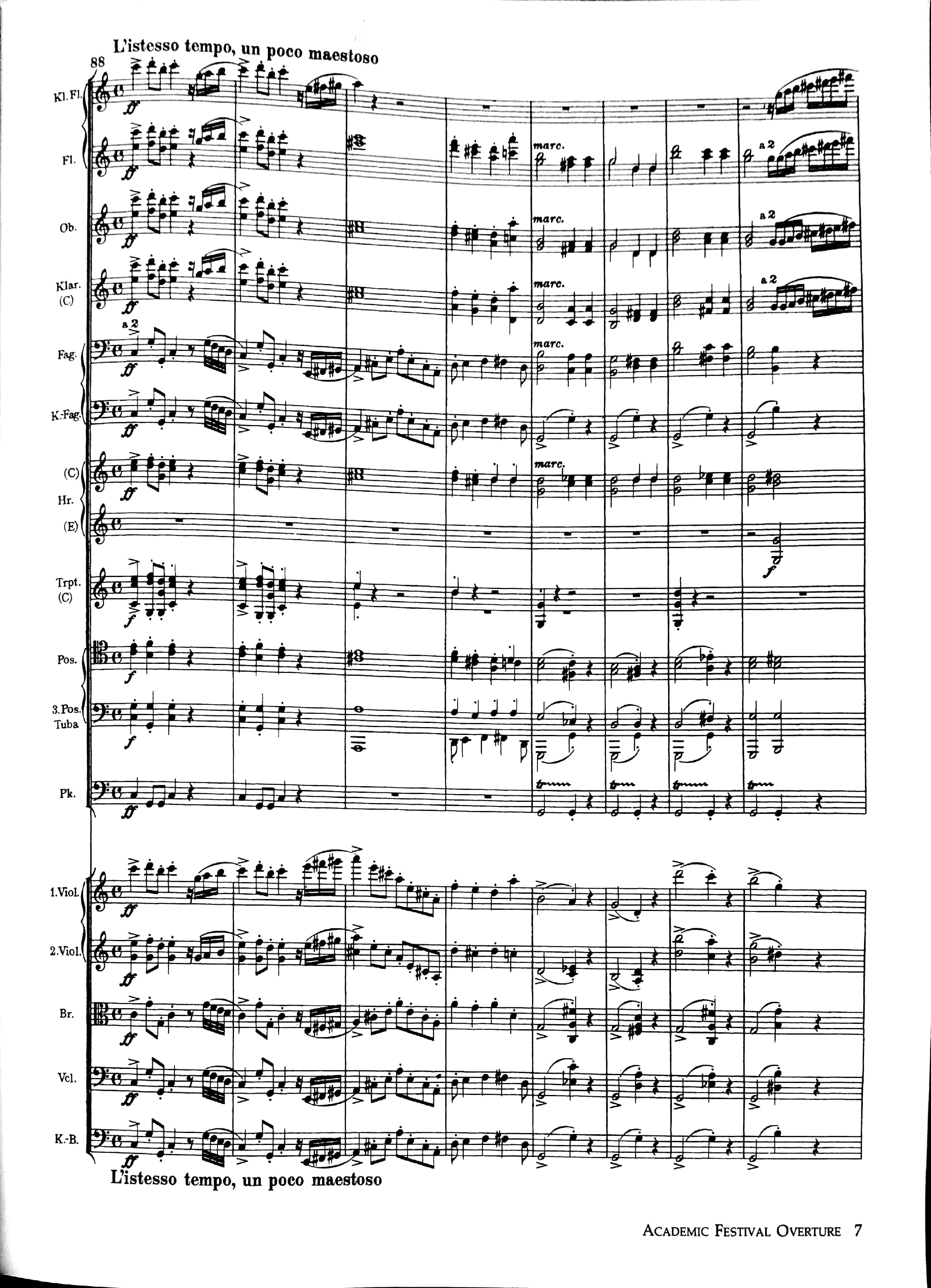

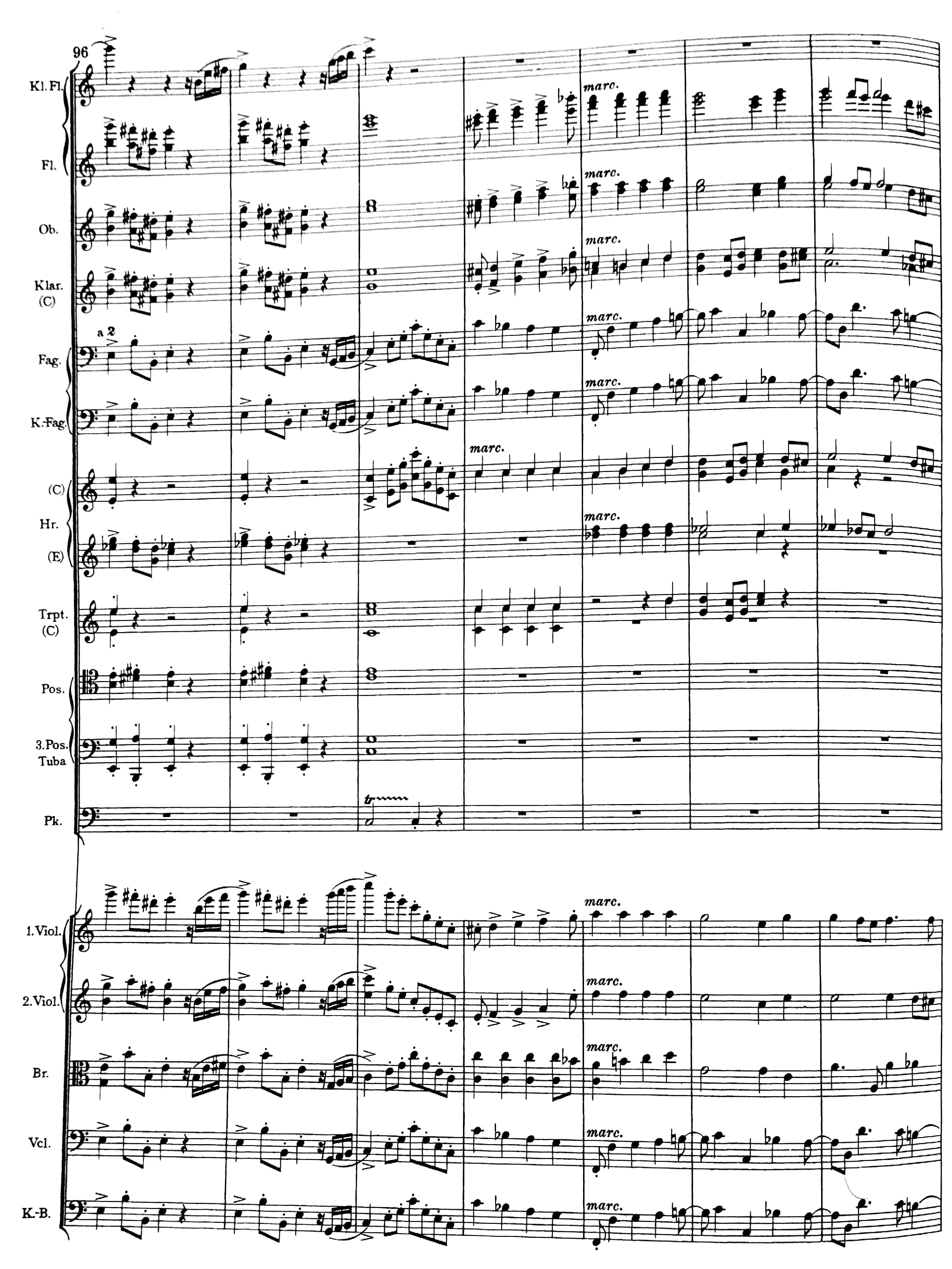

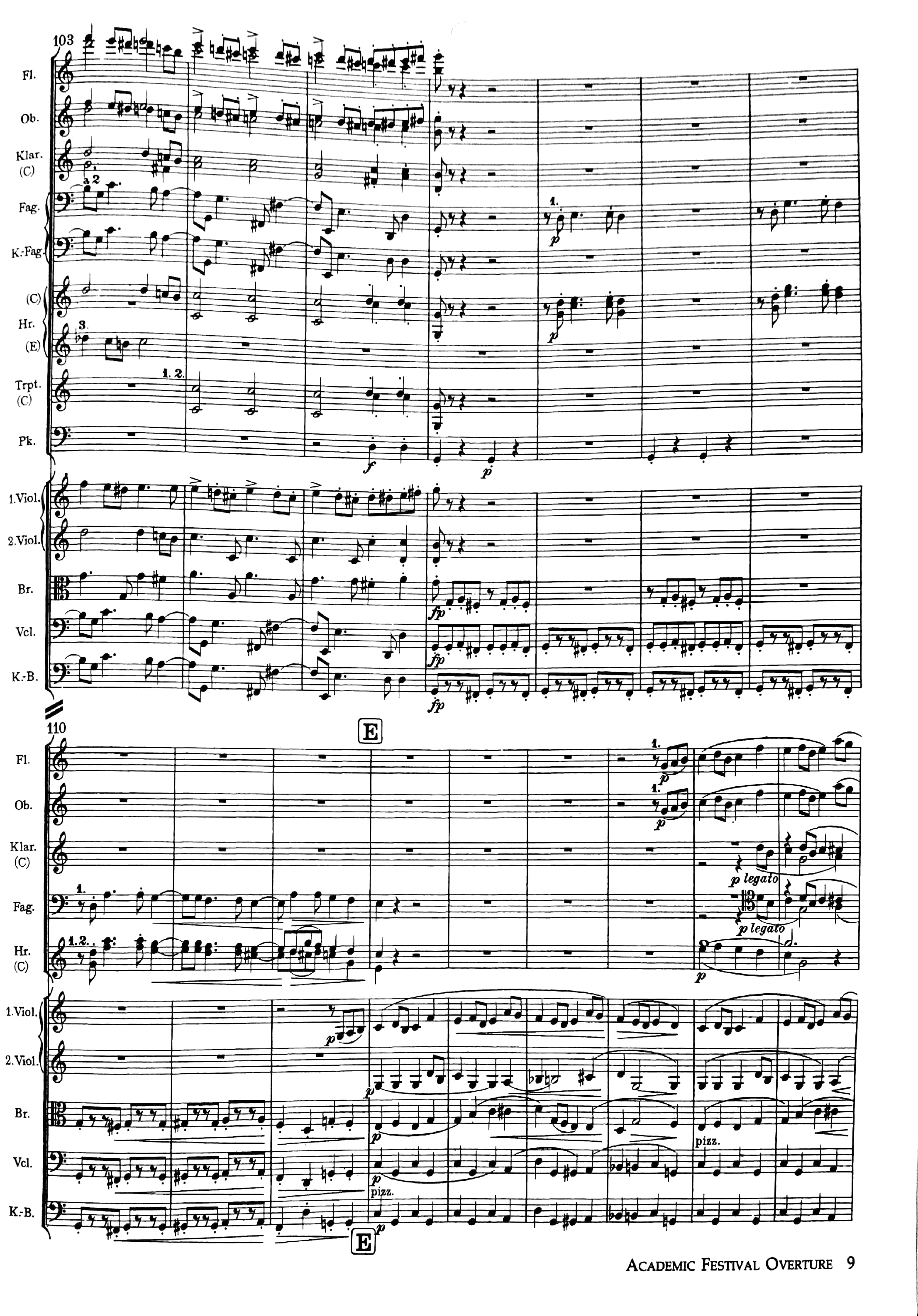

Brahms, in fact, is next. His Academic Festival Overture is a search for symmetry within a sprawling medley of song. The excerpt here is a prime example of this search frustrated by dominant function. C major (m. 88) drops a major third to A major, then a second to G major, the dominant. So far so good, but will Brahms be able to symmetrize? He begins again, promisingly, in E minor (m. 96, a diatonic iii), a major third above C. But instead of filling in F major for the full symmetry (a tempting diatonic IV, no less!) he repeats the major-third drop, this time to C major, and then trips bizarrely through Bb to D and G, landing on his butt back on the tonic C. Hindsight is 20/20, so we know that E minor could only have been a deceptive cadence that needed the secondary dominant D major to set it to rights. Still, the effect is squirmy. What Brahms does more comfortably in Academic Festival Overture is inhabit the realm of fours.

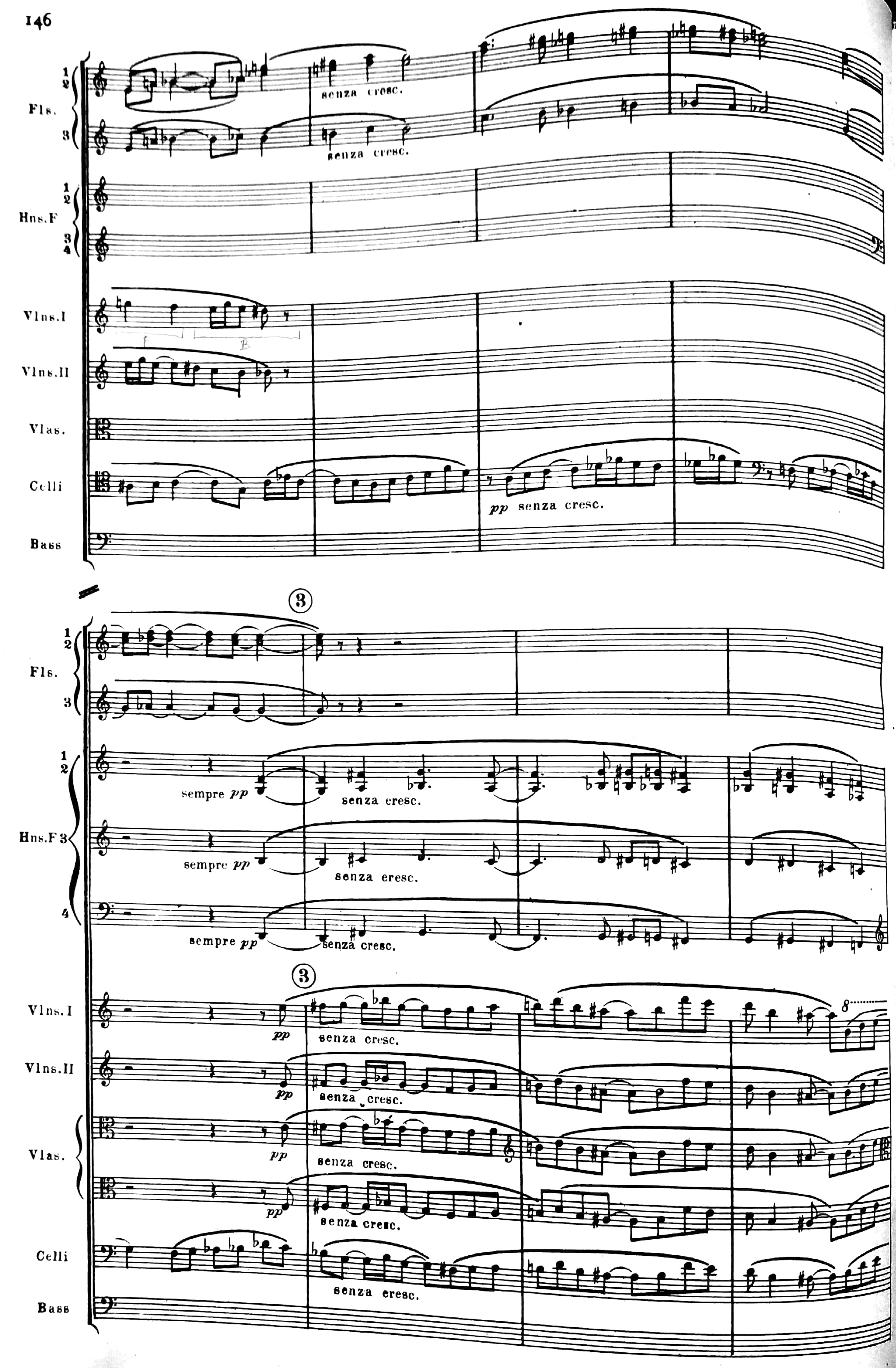

Mozart Quintet G minor K. 516, m. 23

Fours: TETRACHORDS

Is it any surprise that a student of Michael Alec Rose would expound on the tetrachord? Before we dive, however, let’s open with Brahms’ own opening.

From the very first figure, we spy fours at work. The first violins have a power-packed first two bars: a four-note neighbor tone figure followed by a descending minor tetrachord. Opening bars like these offer nearly infinite versatility in the tonal sphere. Brahms, the ironic academic, takes the technical path of least resistance. No tonal shenanigans, no points of imitation, just a repetition in the dominant. Is he already jesting at the fact that he will never quite contend with dominant asymmetry? Maybe. After all, right under our nose, the first two statements are 3-bar phrases! It seems that there’s self-conscious asymmetry even in Brahms’ squarest motivic statements.

Brahms, Academic Festival Overture

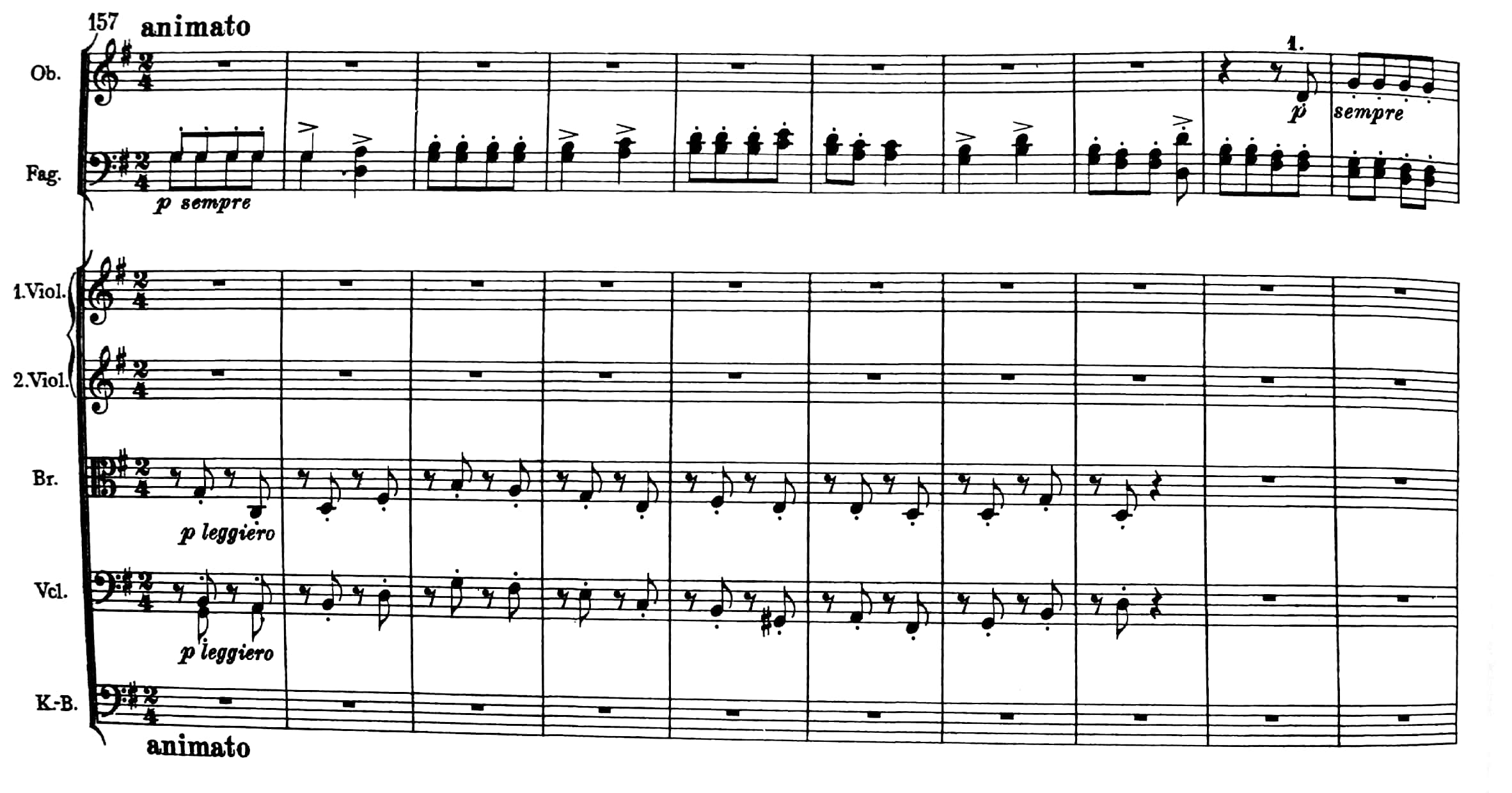

Just for another synechdochal example, take the cutesy bassoon solo at m. 157. What could be more foursquare than a march? Until, that is, Brahms, adds an extra bar at the end (m. 165), just before the oboe’s point of imitation. If asymmetry’s built into harmony, Brahms thinks to himself, then, well, form must reflect content—an extra bar it is. And just like any principle in this composer’s oeuvre, it’s utterly pervasive in the Overture, in ways that this lecture will not address.

Know what else features a descending tetrachord? Our Mozart piece, at last. Our excerpt begins at 12:48.

MOZART

Consider my Adagio, forthwith:

Five players and their slice of your Creation.

The second bar alone does give us good:

A tetrachord, with ornaments, descending

From B flat (dominant) to F below.

JESUS

Then, following the downward rush of [measure] 4,

Your chromatism brings it home in [measure] 7.

MOZART

How could I let it pass? Ascent, descent,

The eros and the pathos and the ludus

Descending tetrachords are but a foretaste.

Let’s onwards to the secondary themes

[measure 18 & 27, and their recapitulatory counterparts],

Descending all the way to tiptoe dancing

Upon the dominant in 32.

Then onward further to Transition Two,

And though it’s in the dominant right here,

In 72 it’ll soon be set to rights.

Here’s the best of our sonata-form:

Like chambered locks the potencies give way,

Until all tensions, sated, dissolve away.

JESUS

But, Mozart, with respect, a tetrachord

Was not the reason this work came to be.

That honor goes to holy number three.

Threes: Divine Flows

MOZART

Do note the grain we ground last Passover,

See how it swells itself upon our table:

Embodied now, the grain’s itself the bread.

JESUS

Likewise a trichord, ascending and descending:

The highest and the lowest changing voices,

This theme embodies your Adagio. [m. 1]

MOZART

Now track my trichord as you’ve tracked your nation.

JESUS

Writ large is your motif’s harmonic motion;

The first two beats [m. 1] encompass all the rest:

One tonic [m. 1], then one dominant [m. 17], then tonic [m. 37].

MOZART

My work is as a rocky seamed face,

Consistent by its very nature, formed

Most carefully, yet all inev’table.

Thus, see the very trichord thrice again,

As upward motion, sol la si [m. 1-2], and then

Truncation in bar 3, first violin,

And languorous elongation in bar 4.

See one seam here [m. 5], a cambiata theme

That frustrates th’ forming trichord with a leap

That seals it tighter for its dissonance.

JESUS

So likewise does a wound that healeth skin

Plain-bind it tighter, even after silence. [m.10]

The break in sound is no longer betrayal

When cambiata’d trichords reemerge [m. 11]

In counterpoint orchestrally prepared. [m. 5-10]

MOZART

And then, Transition One, we have our first

Bedazzling instance: triad as trichord,

Here [m. 17], see this sev’n diminished 6 of V.

The instability, the eros blind.

JESUS

And every descending line, from here

Through Exposition and the sewn-in Recap,

Is true rendition and remembrance fond

Of trichord, trichord, trichord?

MOZART

Verily!

JESUS

But where, oh, does it end?

MOZART

It’s infinite.

My urmotiv expands to fill a canyon, [Coda, m. 76]

And shrinks to fit a thimble, [chromatic descent, m. 37] if I ask.

It’s elemental, just like Claude Lorrain’s

Good study of a stream.

JESUS

Its levels three,

The first far ‘way above our heads, and then,

The second before our feet, and then the third,

A stone’s throw to the right. Your urmotiv

Is plain to see.

MOZART

And water washes still, in motion contr’y

As if it were a pair, violin and cello,

In measure 1 of my Adagio.

Adagio indeed these waters flow,

And eddying, ebbing, falling, never standing

Not for a moment’s rest, like time’s swift flow.

So easily it goes, while I’m at ease.

JESUS

If immortality you seek, go find

Some antic Roman who’ll remember you.

But try instead to see the unity

Your fertile mind has conjured while at work.

For God did grant you not a perfect life,

But a perfect road, and travel it you must.

For see the end that you yourself created.

MOZART

Sure, final vindication long-awaited: [m. 78]

Scar-tissue cambiata healing brings,

Behaving as a tree’s rich cambium

A “secondary thickening” that binds

Each measure in an anacrustic turn;

The final bars full bound together thus,

The trichord realized as healing salve.

JESUS

And all creation bound together thus,

The singularity from whence it came.

I6/4 to I: see, one, two, three! [m. 78-80]

Then I to V4/3: see, one, two, three! [m. 80-81]

Then I, I, I. A trinity divine,

Thrice witnessed, so, my brother, you are mine.